Prodigies—those precocious children who possess musical skills that astound and confound us. Mozart was one. Clara Schumann, too. Today we have Alma Deutscher.

Born in England in 2005, Alma is an accomplished violinist, pianist, and composer. Yes, composer. She wrote her first piano sonata at age seven, an opera at ten. An opera requires a full orchestral score, so she had to know the range and capabilities of all the instruments.

Here she is playing the piano at age 6:

I’m sure she’s not the only 6-yr-old child who can play this Haydn piece, but her playing is extraordinary. Nuanced, beautiful.

A 8, Alma was a guest on The Ellen DeGeneres Show. She showed Ellen the jump rope that helps her compose. “I wave it around and memories pour into my head.”

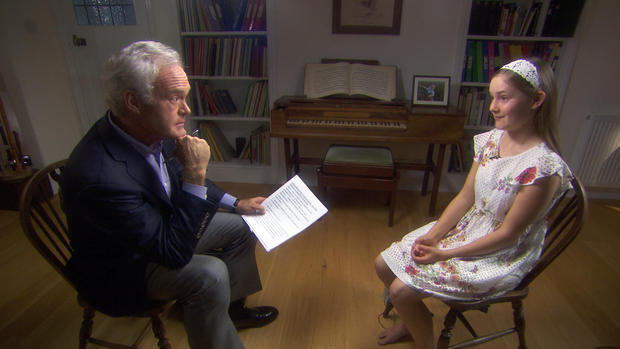

Then came a 60 Minutes profile of Alma. When asked where her musical ideas come from, she told correspondent Scott Pelley, “It’s really very normal to me to walk around and have melodies popping into my head.”

I love getting the melodies. It’s not at all difficult to me. I get them all the time. But then actually sitting down and developing the melodies and that’s the really difficult part, having to tell a real story with music.

She went on to explain that imaginary composers live in her head. In fact, she has made up a whole country where imaginary composers live.

Sometimes when I’m stuck with something, when I’m composing, I go to them and ask them for advice. And quite often, they come up with very interesting things.

When Alma sat down at the piano and invited Pelley to select four notes out of a hat, and then improvised a piece based on a melody consisting of those four notes, he looked like he was wondering if he’d been tricked. He had not.

After appearing on 60 Minutes, Alma’s popularity soared. She has her own YouTube channel. You can find plenty of performance videos there.

Of course, I love Mozart and I would have loved him to be my teacher. But I think I would prefer to be the first Alma than to be the second Mozart.

Alma makes her Carnegie Hall debut on December 12, 2019. She’ll be 14 years old and will play a program of her own compositions. Tickets have been sold out for months.

Paulette Bochnig Sharkey